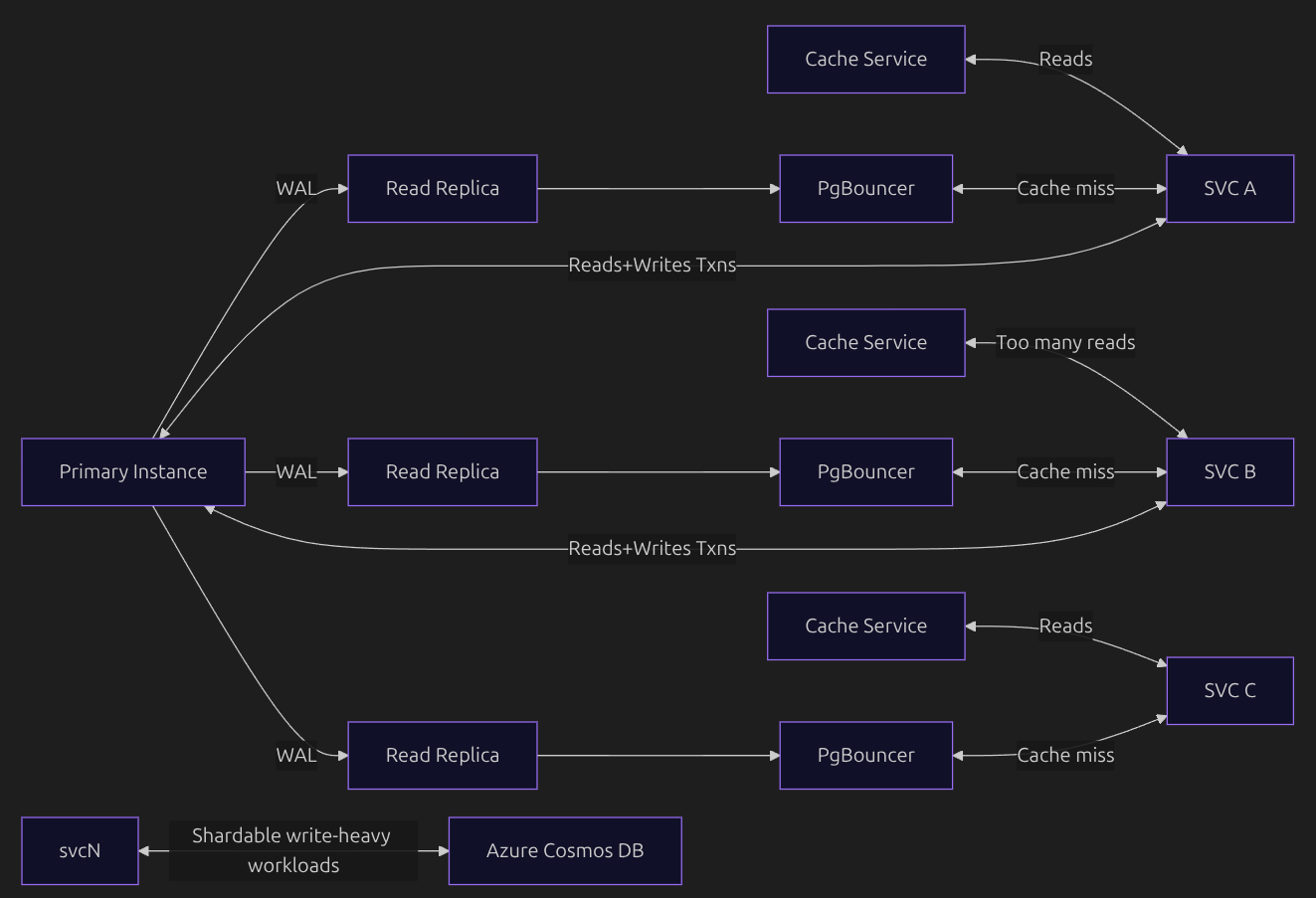

In this article, you will learn about how OpenAI scaled their Postgres database cluster using only one primary instance and multiple read-replicas. First, please take a close look at this simple architecture. Then you will understand each and every components in it as you read further.

The Basic Idea

Multiple services are there to read from the DB, so why hog just one instance for all the read requests? That is why they have multiple read replicas which have the data replicated from the primary instance and can serve read requests in a distributed fashion. On top of that, they have a cache layer to make this process more efficient. Write requests from the service go to the primary instance, so that the primary is always updated with the latest data and can replicate the latest data to the read replicas. Some workloads which are shardable and write-heavy are offloaded to a different DB instance, i.e., Azure Cosmos DB (which takes care of all sharding and related concerns).

Now, let's deep dive.

Primary Instance

This is the instance responsible for:

- Handling all write requests from services, so it always has the latest data.

- Replicating the latest data to read replicas using WAL (Write-Ahead Logging, you will learn about it later in this blog).

Why some of the reads are still going to the primary instance?

Some of the reads are part of a transaction which involves writes, so the whole transaction goes to the primary instance. Simple example:

BEGIN;

SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 1;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 500 WHERE id = 1;

COMMIT;

Read Replica

These are the instances which only take care of read requests from the services. They have the data replicated from the primary instance using WAL. But what is WAL?

Write-Ahead Logging (WAL)

Write-Ahead Logging (WAL) is the mechanism that makes database writes durable and replicable.

The core rule of WAL is simple:

Changes are written to the log before they are written to the actual table.

When a service sends a write request to the primary instance, the database does not immediately modify the table. Instead, it first appends a record describing the change to the WAL file. Once this WAL record is safely written to disk, the write is considered committed. The actual table pages may be updated later, in the background.

This guarantees that even if the database crashes, it can replay the WAL and recover all committed changes. The WAL file is append-only, which makes writes disk-efficient.

How do the read replicas replicate data from the WAL?

Read replicas stay in sync with the primary by consuming and replaying WAL records. They do not copy table data directly. Instead, they apply the same sequence of changes that happened on the primary. By replaying WAL in the exact order it was generated, replicas converge to the same state as the primary. Each read replica keeps track of how far it has progressed in the WAL stream.

The "Noisy Neighbor" Problem

In the above architecture, you can see that service B performs a lot of read requests from the DB, which might affect the performance of other services reading from the same replica. To solve this, they use a workload isolation strategy by routing read-heavy services to separate read replicas.

Why Cosmos DB?

The Core Problem with Write-Heavy Workloads

In a traditional primary–replica setup:

- All writes go to one primary

- Read replicas help scale reads

- But writes do not scale horizontally

As write volume grows, the primary becomes the bottleneck and vertical scaling hits its limits. For some workloads, this model simply doesn’t scale.

Cosmos DB is designed to be horizontally sharded by default and is also multi-writer capable. Writes are distributed across shards using a partition key, removing the single-primary bottleneck.

What "Shardable" Really Means

Suppose you want to store profiles of users residing in different towns. You can partition the database using the town name as the shard key. This way, writes for one town are routed to a different partition than writes for another town, so they don’t interfere with each other. As a result, the database can serve writes for each town independently and at scale. Such write workloads are known as shardable.

Cosmos DB thrives in exactly this scenario.

Caching

Trust me, caching needs no introduction at all. But you will learn something new here too.

Think of a situation where a cache key has just expired and a large number of read requests arrive that depend on this cache key. A cache miss redirects these requests to the DB, causing an unnecessary spike in read traffic.

Solution: Cache Locking and Leasing

Since many read requests are coming in (say, 1000), only one of them acquires a lock on the cache and goes to the DB to read the data and repopulate it. Once this request completes, it releases the lock so that the other requests can read the data from the cache instead of the DB.

Great, isn't it? This reduces the number of DB reads from 1000 to 1.

But what is leasing here?

Locking and leasing is a technique in which the lock is acquired with a TTL (time to live), so that if the request holding the lock fails, other requests will not wait indefinitely.

Connection Pooling

Databases like PostgreSQL handle queries efficiently, but database connections are expensive. Every new connection requires network resources and increases latency. In Postgres, every new connection spawns a new backend processes/threads that consumes the CPU. If hundreds or thousands of application instances open connections directly, the database can get overwhelmed.

This is where PgBouncer comes in.

What PgBouncer Does

PgBouncer is a lightweight connection pooler that sits between your application and the database. PgBouncer:

- Maintains a small, fixed pool of database connections

- Reuses them across many client requests

- Prevents connection storms on the database

Why Connection Pooling Is Necessary

PostgreSQL cannot safely handle thousands of active connections. Without pooling, each service instance opens multiple connections, services are unable to re-use the connection which is free. Making new connection every time consumes network bandwidth as it is a network call, hence increases latency. The database server can hit the max_connections limit.

PgBouncer caps and reuses connections safely.

Why You Can’t Use One Global Database Connection per Service

Postgres connections are stateful. Each connection carries session state, including:

- Active transactions

- Locks

- Isolation levels

- Temporary settings

Services handle requests concurrently, and if concurrent requests use a single global DB connection, they will interfere with each other.

If all requests share one connection:

- Only one query can run at a time

- Other requests must block and wait

- Latency increases linearly with traffic

This is one of the architectures you can use to design a database cluster that scales well and serves millions of QPS (queries per second). I hope you took something valuable away from this blog.

- Piyush